Picture this: you’re complaining to your girlfriends about your birth control options over coffee, and someone says, “Well, at least we’re not using crocodile dung anymore!” Sounds ridiculous, right? But the history of women’s birth control is filled with methods that would make your jaw drop—and honestly, make you grateful for what we have today.

The history of women’s birth control spans thousands of years and crossed every culture, country, and religion you can imagine. From ancient Egypt to medieval Europe to modern-day innovations like Caya, women have consistently refused to let biology determine their destiny. What’s truly remarkable is how similar the goals remained across these vastly different societies: women wanted control over when and if they became pregnant.

Ancient Ingenuity: When Women Got Creative Across Cultures

Let’s start with some definitions. What exactly is a “pessary”? A pessary is a device inserted into the vagina, and when used for contraception, it creates a barrier to prevent sperm from reaching the cervix. Think of it as the ancient version of a diaphragm—women figured out thousands of years ago that blocking access to the cervix could prevent pregnancy. Sometimes it was a solid cap-shape, and sometimes round with a hole, like a bagel (only way smaller, obviously).

The Egyptians: Masters of the History of Women’s Birth Control

The ancient Egyptians were basically the pioneers of documented women’s contraception. Around 1850 BCE—we’re talking nearly 4,000 years ago—Egyptian women were mixing crocodile dung with honey to create contraceptive pessaries, as documented in the ancient Kahun Gynecological Papyrus. (Image above.) It sounds gross but there was actually some science here. The dung created a physical barrier over the cervix, while honey has natural antibacterial properties that helped prevent infection.

But that wasn’t their only innovation in the history of women’s birth control. Egyptian women also created what were essentially the world’s first contraceptive tampons using acacia leaves, honey, and lint, as described in the Ebers Papyrus from 1550 BC. Here’s the amazing part: modern scientists have confirmed that acacia actually has spermicidal properties and is still used in some contraceptive jellies today. So while the delivery method was… rustic… the ancient Egyptians were genuinely onto something scientifically sound.

Cross-Cultural Innovation in Women’s Contraception History

What’s fascinating about the history of women’s birth control is how different cultures independently developed similar barrier concepts, proving that women everywhere were determined to control their fertility.

In ancient India, women created cervical plugs using rock salt mixed with honey, as documented in 8th-century medical texts. The salt acted as a spermicide while the honey helped it adhere—essentially the same barrier principle the Egyptians were using, but with locally available materials.

Meanwhile, Jewish women were crafting reusable barrier methods using sea sponges wrapped in silk with strings attached. This was probably one of the more comfortable ancient methods, and honestly not that different from some modern contraceptive sponges.

Greek women had access to the legendary silphium plant—an oral contraceptive that was supposedly so effective it was worth more than its weight in silver. The demand was so high that by the first century CE, they’d literally harvested it to extinction. Talk about a victim of its own success in the history of women’s birth control!

The Barrier Method Concept Spreads Across Continents

Ancient Wisdom or Ancient Weirdness?

Some methods in the history of women’s birth control crossed the line from practical to completely bizarre. Medieval European women would wear amulets made from weasel testicles around their thighs, believing this would prevent pregnancy. Spoiler alert: it didn’t work. But it shows just how desperately women across cultures wanted control over their fertility—they were willing to try literally anything that promised results.

When Religion and Politics Tried to Stop the History of Women’s Birth Control

Here’s where the story of women’s contraception gets both fascinating and frustrating. These methods weren’t just spreading naturally through cultures—they were surviving despite massive religious and political opposition.

During medieval Europe, the Catholic Church deemed all birth control immoral. But women didn’t just give up. They went underground. Knowledge about contraception in the history of women’s birth control was passed from midwife to midwife, from mother to daughter, in whispered conversations and coded folklore.

This pattern repeated across cultures and religions. In ancient China, women shared herbal contraceptive knowledge despite official disapproval. In the Islamic world, scholars like Avicenna documented contraceptive methods in “The Canon of Medicine,” (shown in the image below) including inserting mint into the cervix as a barrier method.

Even more shocking? In the United States, birth control was completely illegal for nearly a century under the Comstock Act of 1873. Women couldn’t legally access contraception until 1965—yes, within the lives of many today’s grandmothers or even mothers—when the Supreme Court finally ruled in Griswold v. Connecticut that married couples had the right to use birth control.

But throughout this entire period in the history of women’s birth control, women kept finding ways. They had to.

The Evolution of Barrier Methods in Women’s Birth Control History

Now here’s where our story gets really good, because barrier methods—the whole concept of blocking sperm from reaching the cervix—have been the most consistently used approach across the entire history of women’s birth control.

The most famous historical barrier method? Giacomo Casanova, the 18th-century Italian adventurer known for his romantic escapades, recommended that his lovers use hollowed-out lemon halves as cervical caps. The acidity could kill sperm, and the shape created a barrier over the cervix. Crude? Absolutely. Effective? Well, let’s just say there’s a reason we moved on to better options. Comfortable? Definitely not.

The First Real Diaphragms: Progress With Problems

The first modern diaphragm was developed in Germany in the 1880s by Wilhelm Mensinga. But here’s the thing—it was designed by a man, for manufacturing ease, not for women’s comfort or anatomy. These early diaphragms were round, came in multiple sizes, required professional fitting, and had stiff springs that made them uncomfortable and difficult to use.

Women had to go to their doctor, get measured and fitted like they were buying shoes, and often struggled with insertion and removal. The design was functional but far from user-friendly. It was a major step forward in the history of women’s birth control, but still prioritized medical convenience over women’s experience.

Margaret Sanger: The Woman Who Changed Birth Control History

Margaret Sanger literally smuggled diaphragms from Europe into the United States, hiding them in oil packaging to get around those Comstock Laws. She opened the first birth control clinic in 1916 and was arrested for it. But she kept going because she understood what the history of women’s birth control had always been about: women deserved choice and control over their own bodies.

The Modern Revolution: When Women Finally Got to Design Their Own Birth Control

Fast forward to the late 1990s and early 2000s, and something revolutionary happened in the history of women’s birth control: researchers actually started asking women what they wanted in a contraceptive method.

PATH, an organization focused on health equity, conducted studies with women around the world to make a better barrier method, Caya. The message was clear: women wanted more control and fewer side effects. They wanted something that worked with their anatomy, not against it.

Caya Represents a True Turning Point in Women’s Birth Control History

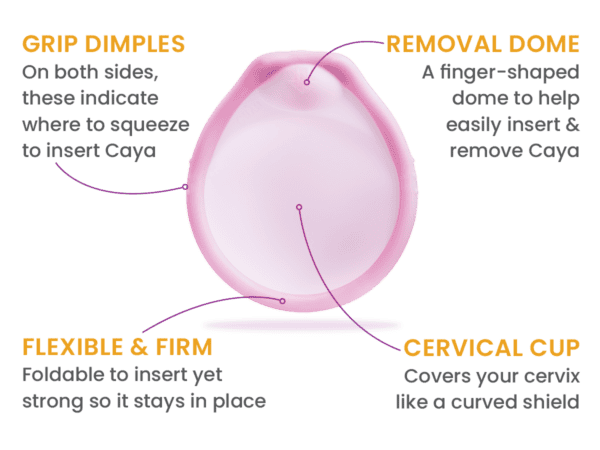

Unlike those 1880s diaphragms designed by men for manufacturing convenience, Caya was designed by women for women. Through a decade-long process that involved testing nearly 200 design variations, doctors and designers consulted with actual women.

The result? A contoured diaphragm that finally addressed what so many women wanted in a birth control method:

Easy Fit: Fits most women without individual sizing (goodbye, awkward fitting appointments)

Easy Insertion/Removal: Has grip dimples and a removal dome for simple handling

Flexible/Comfortable: Features a flexible rim that’s comfortable for both partners

Durable: Made from medical-grade silicone that lasts up to two years

Women tested every element—the materials, the shape, the spring design—until they got it right. It’s literally the first time in the history of women’s birth control that women were the primary designers, not an afterthought.

Why Barrier Methods Keep Winning Throughout Women’s Birth Control History

Looking at the entire history of women’s birth control, one thing becomes crystal clear: women across every culture, religion, and time period have consistently sought barrier methods because they offer something unique—immediate control.

Whether it was an Egyptian woman using honey and acacia, a medieval woman inserting mint, or a modern woman choosing Caya, the appeal has always been the same:

- You control when you use it

- You control when you don’t

- No daily pills to remember

- No hormones affecting your body

- Easy to stop using when you decide you want to become pregnant

From Ancient Pessaries to Modern Innovation: The Caya Difference

The journey from crocodile dung pessaries to Caya represents thousands of years of women refusing to accept “this is just how it is.” Every generation of women built on the knowledge of those before them, improving and refining the basic barrier concept until we arrived at something that actually works beautifully.

Today’s Caya diaphragm represents the best evolution in the history of women’s birth control. It’s hormone-free (no more experimenting with toxic substances), woman-controlled (no more depending on withdrawal or superstitious amulets), and actually comfortable to use (goodbye, stiff metal springs and awkward fittings).

Most importantly, it was designed with extensive input from women who understood that effective birth control isn’t just about preventing pregnancy—it’s about giving women the freedom to make informed choices about their bodies and their futures.

Making Women’s Birth Control History

When you look at the complete history of women’s birth control, one thing becomes obvious: women have always found ways to take control of their fertility, no matter what obstacles they faced. Caya represents the best of this long tradition—combining the time-tested effectiveness of barrier methods with modern design innovation and the wisdom that comes from actually listening to women. There are so many more reasons why Caya is being chosen by women.

So the next time you’re having that coffee conversation with your girlfriends about birth control options, remember: you’re part of a tradition that goes back thousands of years. The difference is, now you have options that actually work well, feel good, and were designed with your comfort and autonomy in mind. It’s also the reason to talk about contraception with your female friends. We’ve helped each other through far worse!

The information included in this blog post is accurate as of publication. For the most current details about Caya, or if you have specific questions about your contraception options, please visit our FAQ at Caya.US.com or consult with your healthcare provider.